Every now and then, I pester my creative colleagues with five questions about their work. Most of these folks are friends, a few are secret enemies, and one has been blackmailing me for years.

Josh Vogt and I met in San Antonio, Texas, at a Worldcon room party. He’d already written “The Weeping Blade” for Paizo’s web fiction, and I had a hunch it wouldn’t be the last we saw of him in Golarion. Sure enough, he soon after published “Hunter’s Folley” and was hard at work outlining Forge of Ashes, the latest of the Pathfinder Tales novels. As if we didn’t have enough in common, I learned he’s also written for roleplaying games and was soon contributing to Privateer Press’s Skull Island eXpeditions.

Once we connected online, I was impressed to see how closely Josh keeps tabs on freelance opportunities, both those that look promising and those about which Admiral Ackbar would warn, “It’s a trap!” Josh is also passionate about fitness, especially encouraging his fellow writers to push away from the desk and stretch our legs now and then.

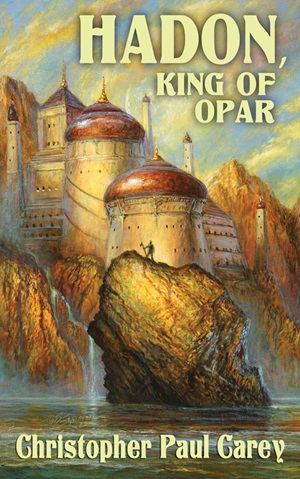

I loved the outline and the few chapters I was able to read while buried under my own deadline, but I’m excited to see the final version of Josh’s Pathfinder Tales novel, Forge of Ashes, available now.

1. Whether it’s a robot or a dark elf, a protagonist ends up being essentially human or else we can’t really sympathize with her. That said, in what ways do you make your dwarf heroine different from human? How about your other non-human characters?

With Akina, there are certainly going to be some “surface level” qualities that set her apart at first glance. Her dwarven strength and heritage, longer lifespan, a sensitivity to the earth itself and ability to see in the dark…all of those sorts of attributes. The dwarves of Golarion also have a fascinating history of how they came to the surface (and what happened to those left behind) and I enjoyed taking Akina through both a physical and inner journey as she discovers just how much that ancient history remains relevant to her. Her reason for fighting is more than mere survival or glory. It’s in her blood.

Ondorum, Akina’s oread companion, was also a delight to create. As an oread, with earth elemental ancestry, he has this inhuman patience that has been further honed by his martial studies. Even though they’re from different races—and possess extremely different temperaments—Akina and Ondorum actually relate to one another in deeper ways with their shared passions and protectiveness of those they truly care for. Some might view Ondorum as naive because of how he tries to treat everyone and everything as possessing of inherent value. It’s a bit of an odd perspective in a world where there are many divisive lines, be it through war, claimed territories, faith, simple banditry, or feuds that go back centuries.

2. You keep an eye on markets and job opportunities for writers, and sometimes I wonder just how much of your time that consumes. How do you balance hustling for work with writing for yourself as well as keeping up with contract gigs?

Actually, in the years I’ve been freelancing, I’ve gotten my gig-hunting process down to be rather streamlined. And I don’t have to be doing it constantly, as I now have past clients who keep bringing work to me. Those times that I do search for new contracts, if I put in a couple solid hours for a few days, I will often pull together enough work to keep me busy for at least a week or two, meaning I can scale back the job hunt again for a while.

With my personal writing, my fiction and all, I will often work to get freelance projects checked off and then give myself a couple days of just focusing on my stories. It lets me be more immersed in the process rather than constantly hopping all around. So it’s less like juggling and more just shifting into one mode for a stretch at a time. Obviously, my hope over the years to come is that I can start focusing more exclusively on my novels and other stories, but freelancing continues to pay the bills!

3. Likewise, you’ve a keen interest in fitness for writers. Apart from the obvious, that is the sedentary nature of the job of writing, how is fitness useful to the craft of writing?

Walking and being physically active in general helps me think. Sometimes when I’m trying to untangle a complicated plot issue, going on a run or hitting the gym can get more blood flowing to the brain. It also takes a little of my direct focus off the issue, so my subconscious might start processing it more and a solution will eventually emerge. I also think doing activities like obstacle course races, martial arts, or crossfit classes are excellent for introducing one’s self to new challenges and learn how to train and persevere—critical qualities for any career writer.

4. How much research do you do when writing for a setting like Pathfinder, which has thousands of pages of setting and rules material? That is, how much is enough without being too much? And how much did you absorb as a gamer before writing a Pathfinder Tales novel?

I’ve gamed much of my life and have been decently familiar with a wide variety of settings from when I was younger. I hadn’t done much since after college, so I did need a refresher. I read through every manual I could get my hand on, focusing first on locations, lore, and creatures relevant to the novel’s specific plot. Then I did some more general research so I could bring in details or mention things a bit further afield from the main action. The fun thing was, a number of items, like city layouts, hadn’t been nailed down in official canon yet, so I was able to develop those details along the way. I also read all the other Pathfinder Tales novels so I had a good idea what what other authors had explored and could see just how in-depth they’d gone. As I wrote, my editor, James, was invaluable and could easily answer any question I had or offer suggestions for particular scenes.

5. How much, if any, does writing for a shared-world setting inspire your original work? Do you ever find yourself reserving ideas for yourself rather than committing them to a project you don’t own or control? Or do you find yourself borrowing or slightly altering your own ideas for both original and work-for-hire projects?

It goes both ways. I always believe the story I’m telling, whether it’s an original setting or shared world, deserves my best effort. So if I have a big inspiration while drafting a tie-in story, I won’t hoard that by any means. There are always more ideas to be had. Honestly, sometimes I can’t use an idea simply because it doesn’t work within that specific world or isn’t allowed by the underlying nature of the game. But in original work, I make the rules!

Check out Josh’s latest news and advice at his website.