Every now and then, I pester my creative colleagues with five questions about their work. Most of these folks are friends, a few are secret enemies, and one has been blackmailing me for years.

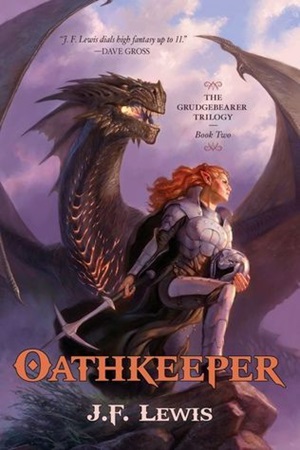

I’d seen the name J.F. Lewis on book covers but new nothing about the man until the good people at Pyr Books sent me a copy of his upcoming novel, Oathkeeper, second in a series begun by Grudgebearer. Instantly I was envious of his Todd Lockwood covers. As I began reading, I realized Jeremy and I had a little more in common than good fortune in cover artists. His epic worldbuilding gave me the impression that he too was a tabletop gamer, a suspicion confirmed by a quick search on his author biographies. Soon after we began chatting, we discovered we had even more influences in common. To wit:

1. Who are some of your main inspirations as a writer?

Corwin from Roger Zelazny’s Amber Chronicles is basically my gold standard when it comes to how first-person narratives ought to feel. If you’re going to put the reader in the head of a protagonist for fifty thousand words or more, that protagonist needs to have a certain amount of snark, wit, and natural-sounding internal commentary. Douglas Adams and Terry Pratchett were very transformative for me, satire-wise. I think all writers tend to pick up story architecture and stylistic quirks from our favorite books as well as the world around us.

Whether it is readily apparent or not, each of my novels explores a series of philosophical questions that interested me at the time I was writing. My core goal is giving the reader a fun ride, though, so I’ve never cared much whether readers picked up on why I was writing something. I think it’s kind of obvious that The Grudgebearer Trilogy deals with questions about slavery, gender and race equality, and parenthood… but it can absolutely be read as an epic vengeance tale with cool fights and snarky heroes.

2. One of the reasons I admire Zelazny is that his writing bridges the divide between clear prose and poetry. When and how often do you feel a writer should indulge in a bit of lyricism for the most powerful effect?

One thing I love about Zelazny is the way he tells just enough for you to know what something looks like without getting lost in graphic word poems focused more on impressing than evoking. When I first write a novel, it doesn’t usually contain a lot of vivid detail. Maybe it’s a Hemingway influence or that I don’t have a movie in my mind when I write or read, but detail doesn’t come naturally to me. Since many readers need more description than I do, I tend to add details with every pass, checking to see if a reader has a good sense of setting. When I start delving into visuals, it is usually because something complex is happening or the imagery is important to convey emotion, character, or plot.

3. Where do you think gaming can help one as a writer of narrative fiction, and where do you think the two arts diverge? That is, what’s a bad lesson one might take from gaming to writing fiction, and how do you resist the urge to indulge your inner gamer while writing a great story?

Basic Dungeons & Dragons in the red box was my first encounter with gaming. That was back with then whole “D&D is evil” thing was happening, and it was laughable how little most people understood about role-playing games. From there I quickly ran through the other boxes, moved on to second edition, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles the RPG, Paranoia, Call of Cthulhu, Middle-earth Role Playing, Rifts, DC Heroes, Marvel Superheroes (the FASERIP version from TSR), Westend Games D6 system, and into more modern systems like Cinematic Unisystem, Pathfinder, Numenara, and Fate Core. I even worked in a comic and gaming store for seven or eight years (the Lion & Unicorn). Amber Diceless Roleplay likely had the biggest impact on me, because the entire emphasis is on the storytelling.

One pitfall into which I’ve seen many aspiring writers fall is the idea of building a game setting and running a campaign set in it with the plan of then turning that into a novel. It can work but often doesn’t and winds up frustrating everyone involved.

Character is the avenue through which I approach story and the plot and world-building all follows from there. In Void City, the characters who defined the setting were Eric and Winter; everything else sprang up around them. In Grudgebearer, it was all about Kholster and Uled until Wylant and Rae’en came along. That’s a common thread for me. Sometimes I have to rewrite massively once I “encounter” the strong female protagonists that always seem to show up in my books. Learning to see through the eyes of a character who might have very different opinions and beliefs than mine clearly had its roots in gaming and was a huge help in writing.

Game balance also informs world-building from a laws of the universe standpoint. My years of Gamemaster practice help me make sure that threats are of the proper scale so that the protagonist, regardless of power level, faces a genuine threat. Since I have always leaned more toward roleplaying than “roll” playing, I don’t usually have to fight against my inner gamer; we’re on the same team.

4. Beyond acting as the adjudicator of player choices, how does the role of narrator of a story differ from that of a Gamemaster or Dungeon Master?

The narratives which are told within a roleplaying game are much more of a collaborative effort than the stories which unfold in a novel or short story. To capture the same group effort in a novel would entail handing over decision making responsibilities for the book’s cast to other people. While I do tend to let my characters (and my players when I’m running a game) drive and or change the plot, my characters are still all mine. Even though they don’t always do what I want them to do, it’s still me making the decisions and I can plan and adapt pretty easily.

When running for a group of players… Well, let me put it this way: If Raiders of the Lost Ark were a novel, we’d know that Indiana Jones is always going to go after the Ark of the Covenant and wind up in the pit full of snakes, but if it were a roleplaying game, there would always be the chance that Belloq would end up down in the tomb or that Sallah would leave his wife and kids to elope with Marian and her pet spy monkey who would turn out to have been a double agent all along.

5. The various species in Grudgebearer fit classic archetypes like elves, lizard men, and plant-people, but they are all a little different. Why do you embrace archetypes while other authors shy away from them? And how do you make them your own?

One of the drawbacks to creating something new is that, as people, we tend to look for familiar ways to relate to things. The Aern in my novels, for example, are metal-boned carnivores who exist as a semi-hive mind dominated by a leader who insists they have free will. If they break an oath, they are unmade. They shed and grow new teeth like sharks and have eight canine teeth (four on the upper jaw and four on the bottom). A whole subsection of their culture is developed to handle the need to keep track of the weapons and armor they forge from their metal bones and those of the dead. They have bronze skin, red hair, and eyes that work more like security cameras than biological eyes. They’re a lot like golems… But they have wolf-like ears, so “elves,” right?

On the surface, the Eldrennai are more typical elves and the Vael are plant people. The Cavair are bat people. The Issic Gnoss are insect people, etc. I know that. But if I’m doing my job right, down the line a reader may encounter someone else’s version of a dwarf or a dragon and think, “That’s not how that should work. In Grudgebearer…” Archetypes are comfortable because of their familiarity, and then as readers learn the unique traits that set these species aside from archetypal forms, they get the chance to really get to know the Sri’Zaur, for example, and see them as something more than the “evil” reptile army they appear to be at first.

It’s up to me to make sure those differences are there and that they are interesting and genuine. As to how I do that, it all springs from character and, since I’m a Pantser, that often means a lot of rewriting as my characters reveal more about their cultural attitudes, history, biology, etc. with those facts informing their actions and driving the story while filling in the details of the setting so that we can see not only what they did, but why, and how, in many cases, they couldn’t have done anything differently while remaining true to themselves. That’s one of the main reasons there is only one actually evil character in the trilogy. Everyone else is just doing what they think is best for them on a personal level or for their people or country.

Look for more of J.F. Lewis’s previous and upcoming projects at his website.